What Isn't Going to Change in 2025

If it didn't work for Ben Franklin, it isn't going to work for you.

I have a bit of a crush on the New York Times illustrator Julia Rothman, and one of the things she’s famous for is those More/Less lists for the new year. You know the ones:

What’s fascinating about them is that you can swipe to see hers going back to 2017, and, as she notes in the caption, they “haven’t changed that much.” In fact, 2018 is just 2017 with “veg every day” added to the “more” side.

In other words, these damn lists don’t work. At all. Ms. Rothman was not able to eat less in 2017 or 2018, nor to eat less sugar in 2022, or “carb load” in 2023, and by 2024 the sugar she plans less of has been joined by “dairy.” “Veg every day” despite being the sole new addition to 2018, didn’t happen — vegetables is on the more list for 2019, again. Other failed intentions for Ms. Rothman include “social media/checking likes/phone time,” “gossiping,” “judgment,” “lateness,” “expectations,” “messes,” and “avoidance.”

Having reviewed her less and more lists since 2017, I feel confident in predicting that Ms. Rothman’s 2025, like mine, will once again feature her having too many unmet expectations and judgments of others, despite her best efforts to change these toxic traits.

Of course, I’m a Jew, and we’re not all down with your Gregorian calendar, so I got all this soul-searching for the year out of the way in October. And at that time, I started an essay that I (perhaps wisely) did not send to all of you, titled, “Yom Kippur is Stupid.” Yom Kippur is all about atonement. The focus is on atoning for the sins of the previous year, apologizing, getting right with people you’ve hurt, making amends, and setting your intentions to do better. I’m a convert, so I’ve only done serious Yom Kippur celebrations for a decade and a half or so. Which is just enough time to notice the scam: If you actually atoned, if you actually were better, if you actually quit being such a dick, the whole holiday would burn itself out in a couple of years. Atonement: We did it. We’re better now. We learned.

Instead, we apologize, get right with each other and God, do all this hard forgiveness work, and then turn right around and start up with some fresh new sinning in the New Year. This is some bullshit, right here. Very human bullshit, but bullshit all the same. Next year, when I stand on the shores of the Mississippi with my handful of bread for the fish, it’s not like I’m going to come up empty. “Hey friends, tashlich is cancelled this year: I was better. I have nothing to confess. I did right this whole year for the first time ever. P.S., if you’re still mad at me about something, I promise I did it intentionally, I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did, and I’m not sorry.”

Failing at even really rigorous attempts at self-improvement has a long history. My favorite example comes from the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin:

It was about this time I conceived the bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection. I wished to live without committing any fault at any time; I would conquer all that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into. As I knew, or thought I knew, what was right and wrong, I did not see why I might not always do the one and avoid the other. But I soon found I had undertaken a task of more difficulty than I had imagined. While my care was employed in guarding against one fault, I was often surprised by another; habit took the advantage of inattention; inclination was sometimes too strong for reason. I concluded, at length, that the mere speculative conviction that it was our interest to be completely virtuous was not sufficient to prevent our slipping, and that the contrary habits must be broken, and good ones acquired and established, before we can have any dependence on a steady, uniform rectitude of conduct. For this purpose I therefore contrived the following method.

In the various enumerations of the moral virtues I met in my reading, I found the catalogue more or less numerous, as different writers included more or fewer ideas under the same name. Temperance, for example, was by some confined to eating and drinking, while by others it was extended to mean the moderating every other pleasure, appetite, inclination, or passion, bodily or mental, even to our avarice and ambition. I proposed to myself, for the sake of clearness, to use rather more names, with fewer ideas annexed to each, than a few names with more ideas; and I included under thirteen names of virtues all that at that time occurred to me as necessary or desirable, and annexed to each a short precept, which fully expressed the extent I gave to its meaning. …

And then, like Maimonides and the principles of faith, he enumerates 13 virtues that might make up perfection. How will he attain them?

My intention being to acquire the habitude of all these virtues, I judged it would be well not to distract my attention by attempting the whole at once, but to fix it on one of them at a time, and, when I should be master of that, then to proceed to another, and so on, till I should have gone through the thirteen; and, as the previous acquisition of some might facilitate the acquisition of certain others, I arranged them with that view, as they stand above. … Conceiving, then, that, agreeably to the advice of Pythagoras in his “Golden Verses,” daily examination would be necessary, I contrived the following method for conducting that examination.

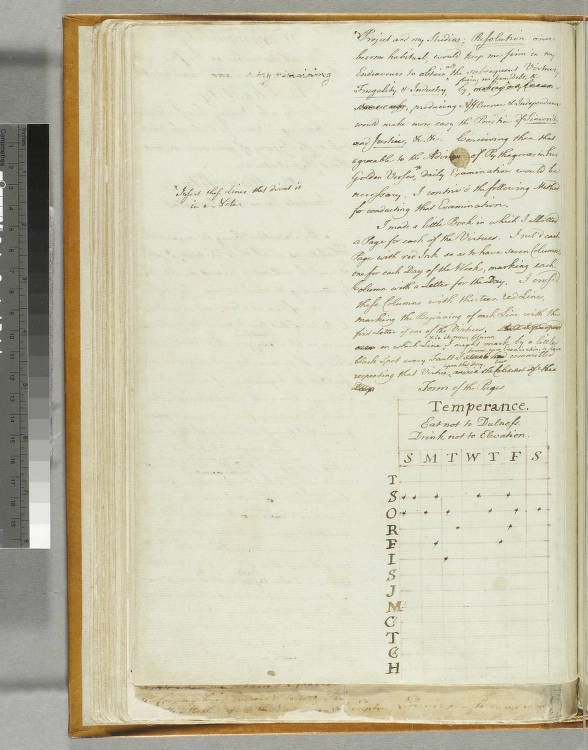

I made a little book, in which I allotted a page for each of the virtues. I ruled each page with red ink, so as to have seven columns, one for each day of the week, marking each column with a letter for the day. I crossed these columns with thirteen red lines, marking the beginning of each line with the first letter of one of the virtues, on which line, and in its proper column, I might mark, by a little black spot, every fault I found upon examination to have been committed respecting that virtue upon that day.

And here Ben helpfully provides us with a little table excerpted from his diary of Sunday, July 1, 1733, where he lays out the 13 virtues and the seven days, with black marks for days he did poorly. (As you can see, he was temperate that whole week, but did not do so great with either silence or order.)

I determined to give a week's strict attention to each of the virtues successively. Thus, in the first week, my great guard was to avoid every the least offense against Temperance, leaving the other virtues to their ordinary chance, only marking every evening the faults of the day. Thus, if in the first week I could keep my first line, marked T, clear of spots, I supposed the habit of that virtue so much strengthened, and its opposite weakened, that I might venture extending my attention to include the next, and for the following week keep both lines clear of spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go through a course complete in thirteen weeks, and four courses in a year. And like him who, having a garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad herbs at once, which would exceed his reach and his strength, but works on one of the beds at a time, and, having accomplished the first, proceeds to a second, so I should have, I hoped, the encouraging pleasure of seeing on my pages the progress I made in virtue, by clearing successively my lines of their spots, till in the end, by a number of courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean book, after a thirteen weeks' daily examination.

Attain Moral Perfection in 13 Weeks sounds like a currently marketable e-course, actually. It charms me that Ben tells us exactly how he set up his 18th century bullet journal, and how he had to transfer the old charts and schedules into a new book suitable for pencil rather than ink, because he had destroyed the pages of the original with black marks and erasures, and how he shows us his daily schedule in the journal, from 5 a.m. (Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness!) to 1 a.m. the following day (Sleep). He discusses how many his faults were and how difficult his task. He even talks about his insecurities that other people would laugh at his efforts or find his plan pious or ridiculous, but nevertheless: “I always carried my little book with me.” His first virtue in the first week was temperance, and his second one was silence, and apparently he got on fine with those. It was in the third week — the week of attaining perfect Order — that Ben’s plan fell apart.

In truth, I found myself incorrigible with respect to Order; and now I am grown old, and my memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want of it. But, on the whole, though I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavor, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it; as those who aim at perfect writing by imitating the engraved copies, though they never reach the wished-for excellence of those copies, their hand is mended by the endeavor, and tolerable, while it continues fair and legible.

A major part of my life’s work has involved helping people accept what they cannot change, specifically their body weight and shape. I have written and spoken and published about the empirical reality that even though there are some people you’ve heard of or met who have lost substantial amounts of weight somehow, you’re just not going to be one of them. Weight loss efforts are like lottery tickets: Even though some people really do win the Powerball, if you want to know what’s going to happen to you tomorrow if you buy a ticket, the answer is: You’re going to lose a dollar. (If weight loss is on your list of New Year’s resolutions, let me promise you: You’re not going to lose a substantial amount of weight. No matter what you do. No, not even if you take those new weight loss drugs. Well, if you take them for a year, you’ll probably lose 10-12% of your body weight, and not any more than that, ever, no matter how long you take them. Also if you ever stop taking them, you’ll gain that 10-12% right back, no matter what you do. They cost $1,300 bucks a month or whatever. Do the math and tell me if that return on investment suits you.)

Doing that work has taught me: There’s a lot of pain in acknowledging that you’re not going to change. And also: A lot can be learned by acknowledging what isn’t changing, what hasn’t changed, and what isn’t going to change. So if you’re a person who sets goals or makes resolutions or makes more/less lists in the New Year, let me invite you to go back over the previous years’ and ask: What didn’t happen? What hasn’t happened for years? Why did things not happen? Are they going to be different this year? What happens if they’re not?

For me, what I learned from this exercise was: my goal attainment is not improving. In 2022 I attained 14 of the goals I set. In 2023, it was 11. In 2024, it was 6. What happened?

Attaining your goals is a function of privilege. Financial privilege, time privilege, even psychological privilege. Marty Seligman spent a good chunk of his career studying first learned helplessness and then optimism, discovering that the first psychological trait inhibited success and goal attainment and the second trait facilitated it. He developed successful depression prevention interventions focused on enhancing optimism. What he’s never, to my knowledge, really explored or incorporated into the model, though, is the fact that optimism is a privilege. It’s a function of life being kind to you, of not experiencing trauma, of not experiencing the conditions of being trapped and exploited that create learned helplessness, both in canines in the lab and in human beings in real life. 2024 was not an optimism-promoting year for me. It was a psychologically exhausting and painful year, a year of loss, and that showed up in my goal attainment.

I also tend to be overly ambitious: I am never going to attain all of my goals for a year. I don’t even expect to. However, I might benefit from better or clearer prioritization, and by reconsidering the balance of “have-tos” versus “want-tos” in my life. One exercise frequently used in ACT psychotherapy is to have clients prioritize their values, and then consider how well they are currently living their values, how much time and energy they are investing in each one. Areas of little importance where you are investing much are areas targeted for change.

Some goals were not attained year-over-year because I really don’t know how to attain them. For these goals, paying for classes or consultants might facilitate goal attainment in 2025.

What about you? Do you have any goals on your list that are not attained year-over-year? What does that mean about you? What does it mean about the goal?

Sometimes it’s about resistance to change, or readiness to change. Ms. Rothman has “eat less,” “eat less sugar,” “less carb load” and “less dairy” on her list year-over-year, as well as “veg every day.” Eat less is simply a non-starter. She’s not going to succeed, and neither are you. But even apart from weight loss: Diet goals are notoriously hard to change. Still, two years ago our household made a major, overnight change in our eating patterns, after I had a serious health scare and my doctor told me the change was required. We’ve maintained it for two years more or less without issue, with some caveats for realistic implementation. Folks with celiac disease or phenylketonuria know: It’s possible to follow even a rigorous and strict eating regimen if you have to in order to survive (as long as it’s not intended to restrict your calories; as mentioned; “eat less” is a non-starter). Most people don’t have the motivation to change their diets because they don’t really need to do so. And if you don’t really need to, why bother? Take that energy you’re wasting feeling guilty about sugar and do something you actually want to do.

Accepting something isn’t going to change — you’re not going to eat less sugar, you’re not going to be less judgmental; you’re not going to fit into your junior high jeans ever again — can be freeing. Reclaiming judgment as discernment; truly and shamelessly reveling in cheesecake and chocolate; buying beautiful new clothes in the size you actually are: These are worthy goals in and of themselves, that may not emerge for you until you let go of pushing towards something that was maybe never in alignment with your own dreams and wishes anyway. Who actually wants to eat less sugar?

What goals and dreams from years past are you not going to attain in 2025? Is there energy you can recover by letting go of them? Is there something better you can have if you don’t have that? Let us know in comments, and, as always, like, comment, subscribe, and share to keep this content coming.